Our 33rd day on the Appalachian Trail was supposed to be our last day hiking—the end of our magnificent trip. I arose early at Brown Fork Gap Shelter with Stuart, our new friend from Austin, Texas. To be precise, I was awakened by Stuart and the sounds of him making oatmeal—in his JetBoil stove. (The word “jet” is key here, because, although I would not have mistaken his camp stove for, say, the high-pitched rumble of a Boeing 737, it does have a distinctive turbine-like sound.)

I checked my phone. It was 6:15 a.m.

“Wow,” I thought. “This guy likes to get an early start.” Inspired by Stuart’s promptitude, I decided I would roust Alexander, and the two of us would get an early start ourselves—on the final leg of our hike, the approximately eleven miles to Fontana Dam.

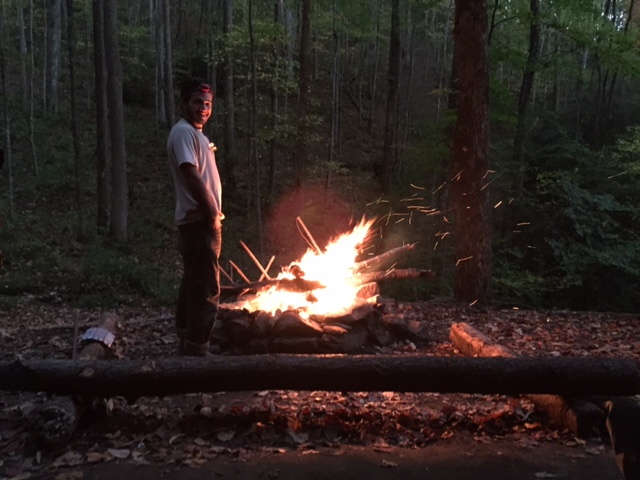

But as I prepared to snatch Alexander from sleep, my thoughts turned to the imminent and pressing end to our journey. I felt a simultaneous rush of sadness and of joy as, in one stream of illuminated remembrance, all the nights and early mornings Alexander and I perched ourselves upon a section of log or flat rock and huddled into the warm space near the fire rushed through my mind. Those moments were the best we have ever experienced as father and son. And it was Alexander who constructed the warm fire-side wombs where we began and ended our days. The four-foot radius emanating from the circle of his fires became a place of peace in which we radiated our love for one another—a safe place for a father and son to connect. When we communed around Alexander’s sacred hearth, we did so free of any personal differences or beliefs that might separate us.

But I had not created even one of those fires—and it occurred to me that it would bring closure of some kind if I were to build our last fire on our last morning in the woods. Then, I thought, I would light the stove, fetch the water, and have the coffee on the ready when I called Alexander. Awakening him to the primitive blessing of fire would be a way to say thanks for having taken such good care of me on this trip.

So, I emerged from the shelter, my headlamp illuminating the forested space before me, and ventured into the predawn world in search of firewood. Wanting Brown Fork Gap Shelter to remember the likes of Teatime and Mama Al and their roaring blaze of an early morning fire, I dragged in the small twigs and sticks and a bevy of large branches that would make that substantial blaze. When I had what I needed, I started huffing and puffing into last night’s bed of coals and arranged the smaller pieces in just the right orientation—until, after fifteen or twenty minutes, the fire caught and we were illuminated.

By the orange light of flame, I watched Stuart make ready for his day. He was an organized hiker. It only took him about five minutes to roll up his sleeping pad, stuff his bag in a sack, make a few adjustments to the straps and assorted buckles on his backpack—and in a flash he was ready to hit the trail. That kind of economy of movement is the product of enviable efficiency and planning.

Me, though, no matter how much I desire to be efficient and organized like Stuart, my entire plan invariably gets tripped up. I get a good start on the morning ritual of packing, but without fail, I notice I’ve forgotten something just as I am coming down the home stretch. Sometimes I get as far as buckling the pack and cinching the straps around my waist before I realize what I have forgotten—usually something that could easily be done away with. It might be just the bag of Q-Tips, or the coffee creamer, or at most my small vial of Advil, yet I go on a bit of a rampage attempting to locate that single item. I have to find it—or I will go mad! Eventually, I regurgitate the contents of my backpack onto the floor of the shelter or the ground around my tent, turn up the object, and start again. On the second pass, I am more deliberate. More focused. I usually get it right. It just takes me awhile.

I have thought a lot about why I do this and have developed two theories. One: the whole packing is kind of a Zen thing—I reorder my internal self by reassembling all of my external parts and gear. Two: I am a complete idiot and cannot remember where I put my stuff.

However, efficient or not, I was true to my inner word—I fetched water from the spring, lit the stove, boiled the water, and made the coffee, as Alexander slept on and Stuart finished his preparations. I was glad to share one last cup of joe with Stuart before he left us. Despite the vast differences in our hiking abilities and woodsman ways, he had proved himself to be kind and generous—quick to share his food, his knowledge, and his experience as a hiker and a fellow human being. He also told great stories about his life as the owner of a carpet-cleaning business back in Austin—managing to make even tales of removing cat piss from the luxurious pile of a Persian rug entertaining.

His coffee finished, Stuart said goodbye, departing camp before the sun was even visible. I watched as he crested the rise to the north, making a little double-time step, like he was an ex-military infantryman with a special little twist to his giddy up. It wasn’t until he pranced out of sight, disappearing behind a stand of hickory trees alongside the trail, that I realized just how much I longed to be like him.

Awash in the electric synthesis of the new day, I could just envision myself, efficient and organized, up and ready before daylight, bristling to attack the trail as soon as there was enough light to make out its winding path through the woods. If I were like Stuart, I could hold my head high at any shelter. I could trade stories of the miles I covered and the techniques I employed to cover them. Hell, I might even adopt that little double-time step of his. Rebrand it as the “North Florida Shuffle” and skip into the forest the envy of other hikers. But even as I longed to be other than a sorry, unorganized morning packer, I knew: I’m not a guy like Stuart, and never will be. As Popeye wisely said, “I yam who I yam.” And I “yam” the guy who will always be the last to depart camp.

Like it or not.

The truth is, there have always been hikers who graced our camp or stopped for a chat along the trail who were simply better than me. Better equipped. More experienced. More suited to the wild environs of the great outdoors. Because, let’s face it, I am a man built for comfort, not for speed. I’m the guy better suited to occupy the hotel lobby when the weather turns ugly. The guy who draws comfort from hot coffee served in a cup and saucer. The guy who knows his way around a breakfast buffet, not the mysterious American Wilderness.

I’ve come to understand that I may be better at writing about the great outdoors than actually remaining in it for too long. The woods frighten me on some intrinsic level. Maybe it’s the intense quiet I find there, or the long, dark shadows that linger throughout the day. Or maybe it’s the bears, the wildcats, or the rattlesnakes. Or maybe something deeper and less definable than that—the sum of the parts of the wild and its unknown threats. But in the past five weeks on the trail, I have also come to understand that I must release comparisons with my fellow hikers or face the gale of an ill wind. On this morning, as Stuart slipped away into the efficiency of his hiking day, I felt safe and mildly confident wrapped in the warm glow of the golden flames of the fire I built myself. I inhaled deeply and exhaled one long and relaxing breath. I felt at peace with myself.

In the midst of these revelations, I sipped a second cup of coffee and witnessed chipmunks scurrying across logs carrying acorns the size of golf balls, birds chirping their little hearts out, and the earliest rays of sunlight filtering through the trees like the golden fingers of God reaching down to make their first contact with earth. When Alexander finally arose, making his way out of his sleeping bag much like a young bear emerges from his first hibernation—yawning, in need of food, and a head of hair that would remain sideways for days—he was touched that I had built a nice fire for him—and even more grateful that I had coffee waiting.

We added more wood to the fire, made more coffee, and Mama Al stirred the last remaining morsels of oatmeal in the pot. And by 9:15, three full hours after I first awoke, when Alexander and I still sat sipping coffee around our flaming fire—not having made one move towards packing our belongings—it became clear that we were purposefully dragging our heels because we longed for one more day in the forest. Without saying a word to acknowledge that our time on the AT was almost up, we pushed back that reality by just being there together, soaking up all the wonder and beauty the forest had to give—as if we were two best friends lingering over the last day of the best summer of their lives.

Finally, at 10:30, we shared a look of utter despair—and rose to ready our packs. Predictably, twenty minutes later, I stood amidst the entirety of my belongings, which were heaped in the middle of the shelter floor. The culprit was a missing bag of G.O.R.P.—our custom trail mix, made mostly of dried fruit, chocolate pieces, and nuts. (In the old days, “G.O.R.P.” actually stood for “Good Ol’ Raisins and Peanuts,” because those were the ingredients one carried in one’s pocket to snack on throughout the day. The original G.O.R.P. relied heavily on M&Ms for an energy blast of sugar. Nowadays, it’s called “trail mix,” but I prefer the old nomenclature. It takes me back to my Boy Scout days in the 1960s, when my beleaguered Troop 36B would disappear into the wilds of north Florida for a weekend of camping, and the G.O.R.P. sustained us even when our alcoholic troop master was too plastered to rally his Scouts for an evening meal.)

Breaking camp that morning was like tearing flesh for us, but sometime after 11, G.O.R.P. recovered, Alexander and I, having succeeded in packing our bags, reluctantly departed Brown Fork Gap Shelter. Normally, Alexander would be in the lead as we made our way down the trail. At least that was the way we had done things since Ryan (aka Treebeard) left our company some 28 days ago. But this morning, Alexander said, “Dad, why don’t you go first.” When I protested, citing my slowness, he quietly said, “Don’t worry. I’ll be right here behind you all the way.”

That was the extent of our discussion about the hours we had remaining to us on The People’s Trail. What Alexander didn’t need to say was, “Let’s do these last miles together, regardless of how slow you have to take it, Dad. The important thing is we do them together because I have loved every minute of being here with you.” He didn’t say it because it was one of those perfect guy moments, when the incumbent structure of our biology overrides the necessity to communicate further.

That—and we both knew that more words would only compound our sadness. I can’t say whether tears welled in Alexander’s eyes, like they welled in mine—because I didn’t look up at him. I just said, “That sounds great,” and moved into the lead position.

The going was relatively easy, with no major climbs, and we made four of the eleven miles to our final destination, Fontana Dam, before stopping for lunch. The cold weather, which had moved in since we departed Nantahala Outdoor Center, had made a major impact on the color of the fall leaves. As we sat on a log, trailside, eating our lunch—a foil pack of Spam smeared with a quarter-inch of Hellman’s mayonnaise and several slices of cheddar cheese—we were stunned by the brilliantly hued leaves flickering all around us, bright reds, oranges, and golden yellows, set against the deep blue of the autumn sky. Alexander surveyed the beauty of our position, and then, mouth filled with Spam, he spat out (along with several bits of dry cracker), “When did all of this happen,” as if the profusion of color had descended overnight.

At that point, we had only seven more miles—just a handful of hours, really—left to spend in the beauty, the grandeur of these woods we’d come to think of as home.

Then my brilliant son asked, “What does Mr. Fucking Guthook have to say?”

(Mr. Effing Guthook—aka “MFG”—is the author of Guthook’s Guide to the AT, the GPS Appalachian Trail app, which had been our main map and source of trail information the entire trip. MFG is a navigation tool—and more. The App gives graphic representations of trail elevation. It would show our location as a little blue dot resting on the side of an uphill or downhill climb—letting us see clearly how brutal or mild the trail ahead might be and how far to the summit or how long the downhill section of trail that would be killing our knees. It also showed our orientation to the trail itself, with a compass arrow. Which was great, because if we happened to have gotten turned around, we could immediately tell we were heading in the wrong direction. Mr. Fucking Guthook would also show the location and distance to the next water source or the next shelter.)

We routinely consulted MFG many times each day. But at this final trailside stop, when Alexander asked, “What does Mr. Fucking Guthook have to say?” I understood him to mean, “How far is the next shelter?”

I consulted MFG. “2.4 miles,” I said, “to Cable Gap Shelter.”

Alexander raised his eyebrows, looked at me and smiled—but he didn’t need to say anything. It was another of those guy moments

“That’s a great idea,” I said.

* * *

About two hours later, around 3 p.m., Alexander and I stopped at Cable Gap, the oldest shelter we had encountered, save the stone building on Blood Mountain. Set just a few yards off the trail, with a stream flowing alongside, it looked like something I had seen on an episode of Little House on the Prairie. An old log cabin of sorts, it was open across the front, with a sloping roof complete with wooden shingles—it was our kind of perfect.

And with that, Mama Al and Teatime settled in for one last night on the AT.

Mom used to fry Spam. What now would cause me to crank the attic fan up to 11 was then a mouth watering signal that supper was nearby. Dad never left the states during Mr. Hitler’s experiment so had not been subjected to the military onslaught of the slimy stuff and enjoyed it with his boys. But I think something in the formula must have changed in the years since. The next to the last can The Child Bride had in her pantry was tried and the last can was never opened and was tossed some years ago. No sense of loss, it just didn’t smell the same and one taste confirmed that the childhood memory was just that. But maybe with cheese…

LikeLike